Bob Sandy: A history in bread and cheese

In 2001, Gabor Sandy at age 86 teaches his granddaughter, Rachel, and her future husband, Sam, how to make challah. /BOB SANDY

In 2001, Gabor Sandy at age 86 teaches his granddaughter, Rachel, and her future husband, Sam, how to make challah. /BOB SANDY

Everything has a backstory, from the shoes on our feet (where were they made?) to the angel illustrations in books (who decided what they look like?), so it’s no surprise that there is a story behind Bob Sandy’s award-winning pumpernickel bread and körözött (cheese) dip.

Sandy’s bread and cheese dip won first place at this year’s World Series of Treasured Jewish Family Recipes cook-off, held at Temple Beth-El, in Providence, on Oct. 25. The judges remarked that Sandy won both for the deliciousness of his bread and dip and for the story behind his recipes.

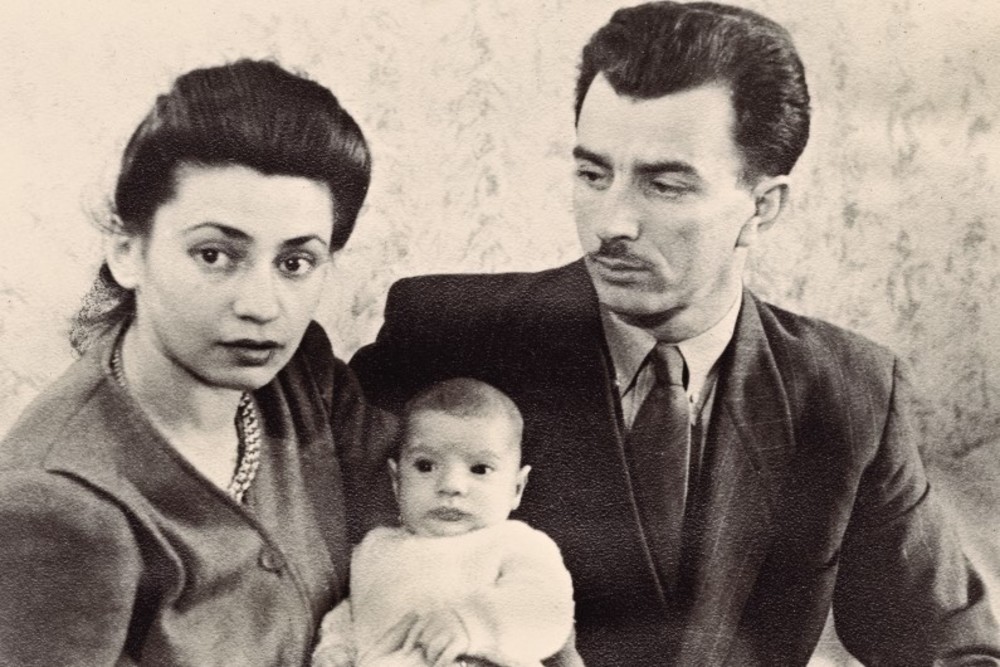

Sandy’s sampling station stood out visually: perched on a shelf next to samples of bread and dip were several old photographs of his family and himself. He used the photos to introduce the story of his family’s migration, his parents’ lives before World War II, and how his father’s baking fed thousands of Hungarian Jews in hiding.

Sandy said his father became a baker because that way, “he knew he would eat.”

Here is Sandy’s backstory:

Sandy, who now lives in Providence with his wife, Elaine, was born to two Hungarian Jews, Gabor and Elizabeth Schwartz, in the Bergen-Belsen displaced-persons camp after WWII. Gabor Schwartz was orphaned at 8 years old, along with two siblings, and started working on a farm at around age 14. Soon, however, he opted to apprentice in a bakery so he would always have food.

After five years apprenticing, in 1934, Gabor found work in a bakery. It was during the depths of the Great Depression, and the unemployed would gather outside the bakery, ready to take a no-show’s job. Conditions were tough, and his boss, who had tuberculosis, tried to scare off Sandy’s father. But Sandy said his dad had an iron will to work.

“He spit in my dad’s mouth and said, ‘I’m gonna get rid of you.’ ” But Gabor figured it would be worse to have no job at all, Sandy said, “so he stayed and never got sick.”

Then the war came. Gabor was drafted into the Hungarian army, and went from there into a forced labor camp, as did Elizabeth. Sandy’s parents met during the war, and their paths crossed again in Budapest at a safe house called the Glass House, where the Swedish and Swiss consuls at the time, Raoul Wallenberg and Carl Lutz, housed Jews and gave them papers declaring them Swedish or Swiss citizens. Through this ruse, Wallenberg and Lutz protected nearly 75,000 Jews from deportation. In the Glass House, Gabor was both a guard and a baker.

After the war, Gabor and Elizabeth went to a displaced-persons camp, where Sandy was born. When he was 2 1/2, the family moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, where Gabor worked in the famous Widoff’s Bakery, which closed its doors this past summer after more than 100 years in business.

When Sandy was 7, his family moved to the booming metropolis of Detroit, and by high school Sandy was working part time in the bakery where his father worked, as well as at other bakeries in the city, learning his way around.

“The idea was if I was going to learn, I had to work all over the place. So I worked at about 20 bakeries, always on the low end on the totem pole,” he recalled.

Sandy worked at bakeries on and off throughout his schooling. In 1977, he got a Ph.D. in economics and from then on worked in various positions at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. He worked his way up from an assistant professor in economics to working in the president’s office and with the State of Indiana’s Higher Education Commission on new degree programs. He was also the liaison to other universities in the state.

After several years of living part time in Indiana and Rhode Island, Sandy settled permanently in Rhode Island in 2013.

Sandy returned to baking as a hobby in retirement partly because he had the time, and partly in an effort to improve on Providence’s offerings of Jewish-style breads: bagels, pumpernickel, rye and challah. These, he says, are the four staples of a Jewish bakery in Hungary. He learned to bake all of them from his father, and he continues to think of them as his “four standards.”

But to enjoy home-baked pumpernickel, Sandy had to scale down the industrial measurements he’d learned from working in bakeries. He even created the caramel color himself and says it took around 20 experimental loaves to perfect the recipe.

“I didn’t have to do all the experimenting with the körözött, as with the pumpernickel, because my mom was here this summer,” he said. “So she [would say things like] ‘you’re not putting in enough onion.’ She knew by tasting it.”

While onions are easy to find, the necessary Hungarian cheese, called liptó túró, wasn’t available in the United States. So Sandy and his mother embarked on a quest for the perfect sheep cheese – that is, a cheese that isn’t too salty.

Now a grandfather, Sandy has a little help of his own: his grandchildren, Sol and Matilda, can be found hanging around the counter where Sandy preps and mixes his award-winning bread.

“My daughter keeps a picture on her mantel of my dad teaching them how to make bread,” Sandy said, explaining that baking has become a family activity. “A lot of times when I make bread, I have my grandson helping me. So if I’m working here and he comes in [and asks], ‘Papa, can I help?’ I get a little stool, and he starts working, rolling out the dough.”

I left Sandy’s home with some of the pumpernickel and körözött. He said it would help me with my story. It was an over-the-top delicious supplement to his family’s story.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The photos attached to this story are only a few of hundreds of family photos saved on Bob Sandy’s computer. We looked over all of them together, including several digitized photos from before the war. After being liberated by the Russian army, those who had sought refuge in the Glass House were given a chance to go to their homes. When Elizabeth Schwartz (they changed their name to Sandy after immigrating) arrived at her apartment, which she said was “about a 20-minute walk if no one is shooting at you,” people were looting the apartment complex, and all of her valuables were gone. But her photos were, luckily, scattered around the property and she was able to salvage them.

ARIEL BROTHMAN is a freelance writer who lives in Wrentham, Massachusetts.