Jewish culture of Eastern Europe is alive and well

My four grandparents immigrated to the United States from Poland and Romania around 1900. My desire to stand on the ground where they grew up increased as I worked on my mother’s family’s history (“Feits and Breitowiches: from Galicia to Chicago,” 2017).

In July, my sister, Ruth, my daughter, Rosanna and I set out to visit their hometowns. We knew that the Holocaust had wiped out almost all the Jews of the region, but we wondered: had it also wiped out Jewish culture there, or were the survivors able to reestablish their communities? We wanted to be awake to the region’s deeply rooted anti-Semitism, which affected our grandparents, as well as the World War II victims. At the same time, we wondered if we could find ways to heal from those traumas, for ourselves, our ancestors and our descendants. Finally, we wanted to know what is happening now, especially in the Jewish communities.

In Iasi, Romania, the Jewish Community Center includes an office with old handwritten records, a museum, and an active synagogue and one used as a social hall and a Kosher restaurant. We learned that from a peak of 44,000 in 1900, only about 300 Jews remain, but they are determined to revive their community.

We were the only patrons at the Kosher restaurant and were served chicken soup. After one taste, my sister exclaimed, “This is Nana Rose’s soup!” We were both brought to tears.

Throughout Romania, the number of Jews is very small. Our guide at the Jewish Community Center said most of her family emigrated to Israel – like most of the Jews who survived the Holocaust – but she was determined to stay and rebuild the community here.

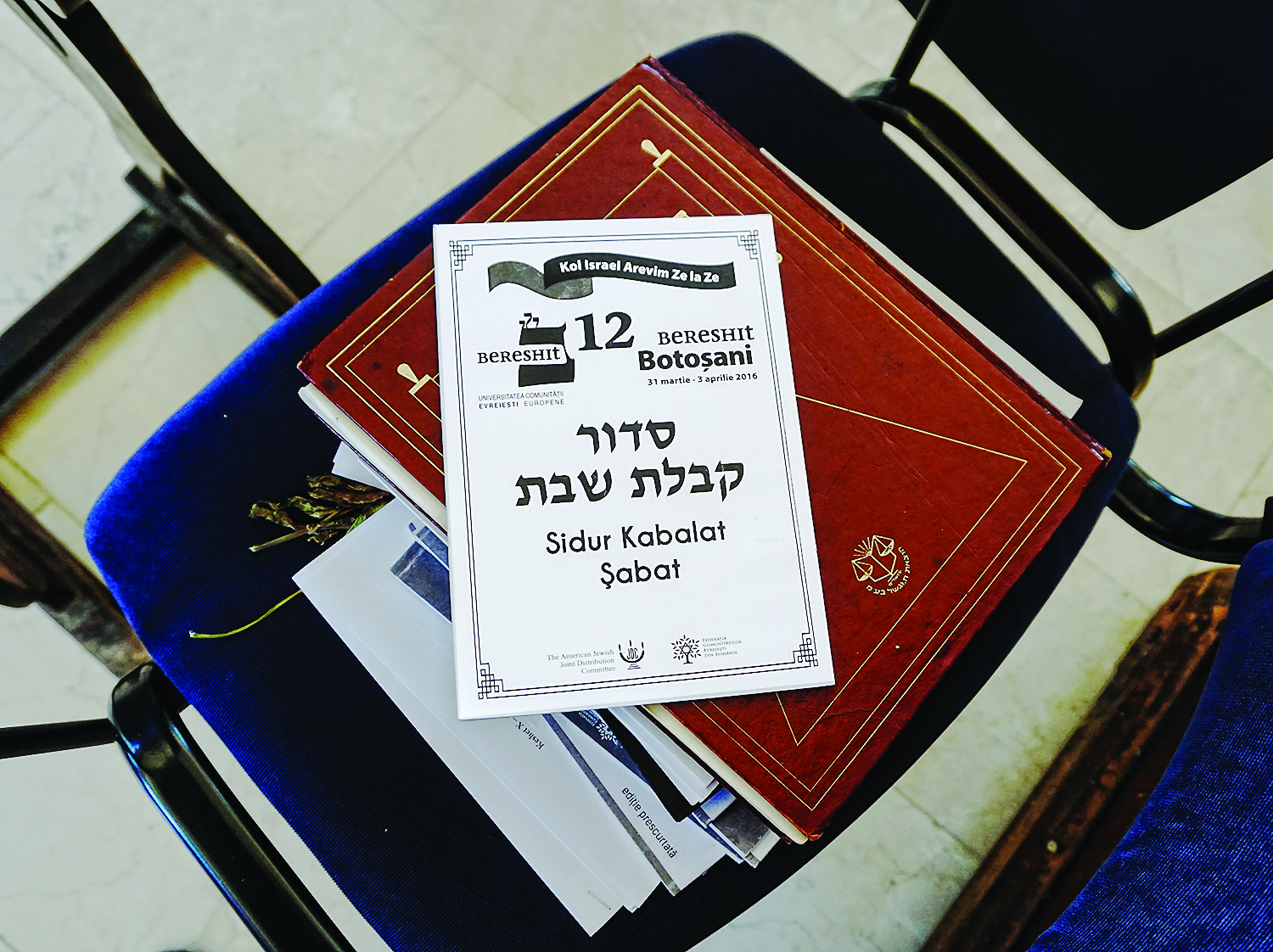

She also told us that the small Jewish communities throughout Romania are in touch with one another; they get together twice a year for a shabbaton. They rotate the venue so that all the communities feel equally important. We were touched by the prayer books created for these events.

In Bukowsko, Poland, we got lost looking for the cemetery and ended up on a hilltop outside the rural village. It’s just a hilltop, with fields rolling on all sides with the forested Carpathian Mountains about 10 miles to the south. Some of the fields had sunflowers in bloom, bright yellow and dazzling. The village is nestled to one side and seems small in proportion to the miles and miles of fields. The air was sweet; it was quintessential summer; green everywhere, crops reaching their peak, ripening under the warm sun. There was stillness, a gentle breeze, obvious growth, fertility, blue sky, wispy clouds. It was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been.

Eventually, we found the cemetery in a forest. At last we were among the Jewish headstones, with a mystical light in a clearing. I focused on how lovingly the cemetery had been restored, but I could also feel the echoes of trauma from desecration and murders that occurred there. I held these opposites as we created an improvised service and recited the Kaddish. I thought of Zlota (my grandfather’s mother, who died in childbirth), her dead baby, and my grandfather’s two brothers, who died young.

In Budapest, on the day of our arrival, a Friday, we hurried to the Aurora Community Center to attend a kabbalat Shabbat service. We knew from our rabbi, Leora Abelson of Congregation Agudas Achim, in Attleboro, that this is a progressive community of young people.

They had use of some property and had set up a beer garden and charitable offices in the building. Profits from the beer garden make it possible to give free rent to the charities, which help refugees and work on LGBTQ issues. Just two days before our arrival, the Romanian government had closed down the beer garden – after raiding it two weeks previously and arresting about 100 people without clear cause.

The service was basically a long sequence of prayer-songs, most of which were familiar to us, as well as to almost everyone present. Loose-leaf notebooks served as prayer books and held the words to songs and prayers in Hebrew and transliterated into Hungarian. The singing was with gusto and ruach (spirit)!

We went around the circle, saying our names and where we are from. More than half the people were Hungarian, but some were from Israel, European countries and the U.S. I sat next to a young woman from Budapest who spoke English and told me that the young people have a renewed interest in Jewish traditions. Their grandparents either perished or barely survived the Holocaust, and their parents didn’t want anything to do with being Jewish. But now this new generation is curious, and when they ask questions and explore their Jewish heritage, they are drawn into taking part. In this particular community, they want to continue the traditions, but make them more egalitarian. They emphasize giving women full voice.

In Krakow, Poland, the Jewish quarter was lively, full of restaurants, hotels, bookshops and synagogues, and sprinkled with Jewish schools. We saw many tour groups and realized that there is a substantial tourist industry for people like us who want to see their homeland or learn about the Holocaust.

At the Jewish Community Center, we saw a restored synagogue, with a courtyard separating it from the community center. The receptionist told us that the community center offers many social events, and attendance has increased dramatically over the last few years. She echoed the woman in Budapest in saying that this new generation wants to connect with its Jewish heritage.

Each year there is a Jewish festival in Krakow, and we saw posters for musical events, including a Progressive Jewish quartet. The Hasidic community, including Chabad, is growing very fast, and a whole spectrum of Jewish groups is emerging.

Everywhere we went on this trip, reminders of the Holocaust were obvious. Despite facing that horror, we came away with renewed optimism. Taking a long view, it seems clear that the Jewish culture of Eastern Europe simply cannot be wiped out. The traditions that we cherish are alive and thriving today.

JOAN WEBB is a member of Congregation Agudas Achim in Attleboro.