High Holy Day Holocaust stories that nourish the soul

Stories from the Holocaust are often horrific, sometimes hopeful and occasionally both. As 5779 approaches, we are sharing some of these deeply touching stories that took place during the High Holy Days.

One brief Yom Kippur story is related in “From Rabbi Huberband’s Diary” (published in English as “Kiddush Hashem,” edited by Jeffrey Gurock and Robert Hirt): In the aftermath of the German invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, all public observances of Yom Kippur were outlawed. Jews debated whether they should open their stores, lest they be accused by the Germans of closing them in honor of the holiday.

According to Rabbi Huberband, Jewish shopkeepers devised a remarkable scheme to avoid doing business on Yom Kippur while eluding the Nazis’ revenge: “Jews’ shops were open. The ‘salesmen’ were all women. Actually, the women didn’t sell anything; people took merchandise, but without paying for it. The women didn’t take any money, but they did on the other hand give away money. They took their tribute payments over to the [Judenrat] office, Yom Kippur being the last day, the deadline for the tribute.”

The following story, “A Shofar in a Coffee Cauldron,” from Yaffa Eliach’s moving book, “Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust,” epitomizes the message that in the hardest and most troubling of circumstances, when all seems lost, that last vestige of humanity – free choice – remains.

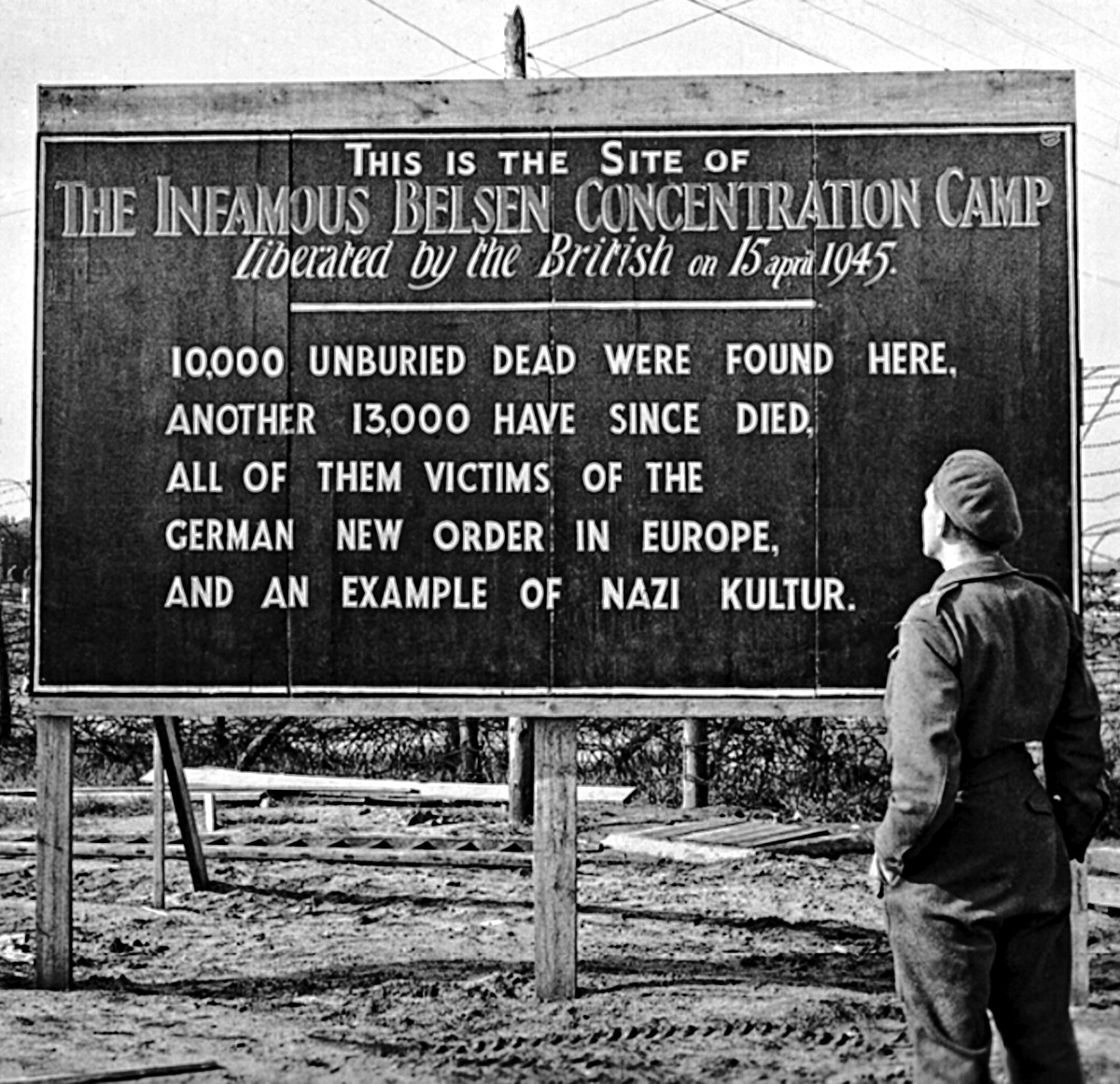

Wolf Fischelberg and his 12-year-old son were walking among the barracks of Bergen-Belsen trying to barter some cigarettes for bread. As they walked, a stone thrown over the barbed wire separating one sector from another landed at their feet. Wolf asked his son what it meant.

“ Nothing! Just an angry Jew hurling stones, replied the son. Angry Jews do not cast stones; it is not part of our tradition replied the father.”

Wolf Fischelberg looked around to see if all was clear and then bent down to pick up the stone. A small gray note was wrapped around it. They walked into a safe barrack, were other Polish Jews lived, to read the note. It was written in Hebrew by a Dutch Jew named Hayyim Borack.

Borack wrote that he was fortunate to have obtained a shofar and if the Hasidic Jews from the Polish transports wished to use it for Rosh Hashanah services, he could smuggle it to them in a coffee cauldron.

The Polish Jews took a vote. Those in favor of the plan to smuggle in the shofar held a clear majority; they were willing to give up their morning coffee ration on the first day of Rosh Hashanah.

At the time and place specified in the note, a stone once more made its way over the electrified barbed wire, this time from the Polish Jews to the Dutch.

“ You see, my son, Jews never throw stones in vain, Fischelberg said.”

The smuggling of the shofar was a success. Nobody was caught and the shofar was not damaged. As Fischelberg’s daughter, Miriam, listened to the shofar, she fervently hoped that it would bring down the barbed-wire fences of Bergen-Belsen, just as the shofar had in earlier times brought the walls of Jericho tumbling down.

When the service was over, nothing had changed; the barbed-wire fences still stood. Only in hearts did something stir – knowledge and hope. Knowledge that the muffled voice of the shofar had made a dent in the Nazi wall of humiliation and slavery, and hope that someday freedom would bring down the fences of Bergen-Belsen and of humanity.

The final story is excerpted from an article, “The Rosh Hashanah Warning that Saved Denmark’s Jews,” written by Lily Rothman for the September 2015 issue of Time magazine.

“After Nazi Germany invaded Denmark in 1940, the idea was put forward by its occupiers that the Scandinavian nation was not in fact occupied. Rather, it was a ‘model protectorate.’

“By the summer of 1943, the resistance was no longer subterranean; fighting broke out in the streets, ending several years of a relatively passive German stance on Denmark’s Jewish population.”

On Sept. 29, 1943 – Rosh Hashanah eve – the Danish resistance pulled off one of World War II’s most notable heroic feats. When Copenhagen’s Jews gathered to mark the holiday, the chief rabbi, Marcus Melchior, canceled the religious services because he had been tipped off that a Nazi roundup was planned for the holiday, when Jews would either be at home or at synagogue. The rabbi urged people to hide or flee.

“What happened next was no secret – at least not after it was over – and there was a short account of the incident in the Oct. 11, 1943, issue of Time.

“Across the narrow waters of the Öre Sund word came to Sweden last week that 1,800 Gestapomen, sent to Copenhagen specially for the job, had broken into Jewish homes and synagogues during Rosh Hashanah, arresting most of Denmark’s 10,000 Jews. The reports said the Germans planned to ship their prisoners to the charnel houses of Poland.

“Next day the Swedish Government told the German Government that there was immediate, unconditional sanctuary for all Danish Jews in Sweden. The Germans ignored the offer. But at week’s end upwards of 1,000 wretched Jews from Denmark had found their way across the cold Öre Sund to merciful Sweden.”

That “upwards” is key: by the count of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, more than 7,000 Danish Jews – out of a population that was just shy of 10,000 – were ferried by fishermen to Sweden – and freedom.

If such acts of hope and faith in one’s fellow man can burn in Poland, in the barracks of Bergen Belsen and Denmark so too can we search for ways to choose our attitudes and transcend our circumstance for the better. In doing so, we show that our choices matter and that what we do with our lives is meaningful.

L’shanah tovah!

LEV POPLOW is a communications consultant writing for the Bornstein Holocaust Center. He can be reached at levpoplow@gmail.com.